The Influence of Charley Patton

Charley Patton is considered by many to be the “Father of the Delta Blues”. He created an enduring body of American music and inspired most Delta blues musicians. The musicologist Robert Palmer considered him one of the most important American musicians of the twentieth century.

Patton (who was well educated by the standards of his time) spelled his name Charlie, but many sources, including record labels and his gravestone, use the spelling Charley.

In 1897, his family moved 100 miles (160 km) north to the 10,000-acre (40 km2) Dockery Plantation, a cotton farm and sawmill near Ruleville, Mississippi. There, Patton developed his musical style, influenced by Henry Sloan, who had a new, unusual style of playing music, which is now considered an early form of the blues. Patton performed at Dockery and nearby plantations and began an association with Willie Brown. Tommy Johnson, Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, Robert Johnson, and Chester Burnett (who went on to gain fame in Chicago as Howlin’ Wolf) also lived and performed in the area, and Patton served as a mentor to these younger performers. Robert Palmer described Patton as a “jack-of all-trades bluesman”, who played “deep blues, white hillbilly songs, nineteenth-century ballads, and other varieties of black and white country dance music with equal facility”.

In 1897, his family moved 100 miles (160 km) north to the 10,000-acre (40 km2) Dockery Plantation, a cotton farm and sawmill near Ruleville, Mississippi. There, Patton developed his musical style, influenced by Henry Sloan, who had a new, unusual style of playing music, which is now considered an early form of the blues. Patton performed at Dockery and nearby plantations and began an association with Willie Brown. Tommy Johnson, Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, Robert Johnson, and Chester Burnett (who went on to gain fame in Chicago as Howlin’ Wolf) also lived and performed in the area, and Patton served as a mentor to these younger performers. Robert Palmer described Patton as a “jack-of all-trades bluesman”, who played “deep blues, white hillbilly songs, nineteenth-century ballads, and other varieties of black and white country dance music with equal facility”.

He was popular across the southern United States and performed annually in Chicago; in 1934, he performed in New York City. Unlike most blues musicians of his time, who were often itinerant performers, Patton played scheduled engagements at plantations and taverns. He gained popularity for his showmanship, sometimes playing with the guitar down on his knees, behind his head, or behind his back. Patton was a small man, about 5 feet 5 inches tall, but his gravelly voice was reputed to have been loud enough to carry 500 yards without amplification; a singing style which particularly influenced Howlin’ Wolf (even though Jimmie Rodgers, the “singing brakeman”, has to be cited there primarily).

Patton settled in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, with his common-law wife and recording partner, Bertha Lee, in 1933. His relationship with Bertha Lee was a turbulent one. In early 1934, both of them were incarcerated in a Belzoni, Mississippi jailhouse after a particularly harsh fight. W. R. Calaway from Vocalion Records bailed the pair out of jail, and escorted them to New York City, for what would be Patton’s final recording sessions (on January 30 and February 1). They later returned to Holly Ridge and Lee saw Patton out in his final days.

Patton settled in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, with his common-law wife and recording partner, Bertha Lee, in 1933. His relationship with Bertha Lee was a turbulent one. In early 1934, both of them were incarcerated in a Belzoni, Mississippi jailhouse after a particularly harsh fight. W. R. Calaway from Vocalion Records bailed the pair out of jail, and escorted them to New York City, for what would be Patton’s final recording sessions (on January 30 and February 1). They later returned to Holly Ridge and Lee saw Patton out in his final days.

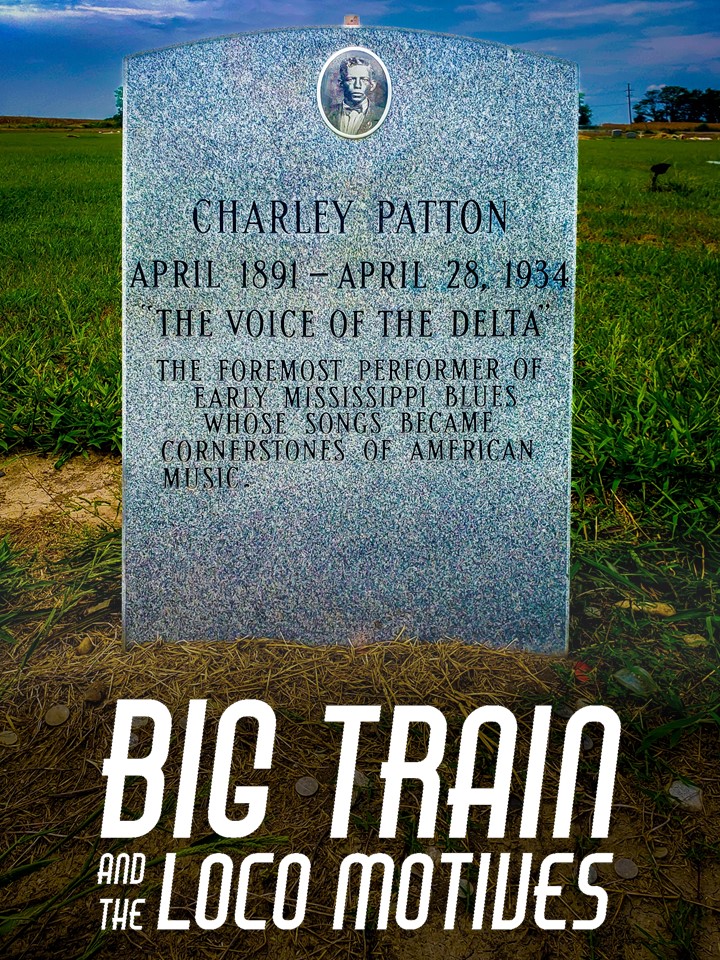

He died on the Heathman-Dedham plantation, near Indianola, on April 28, 1934, and is buried in Holly Ridge (both towns are located in Sunflower County). His death certificate states that he died of a mitral valve disorder. The death certificate does not mention Bertha Lee; the only informant listed is one Willie Calvin. Patton’s death was not reported in the newspapers.

He died on the Heathman-Dedham plantation, near Indianola, on April 28, 1934, and is buried in Holly Ridge (both towns are located in Sunflower County). His death certificate states that he died of a mitral valve disorder. The death certificate does not mention Bertha Lee; the only informant listed is one Willie Calvin. Patton’s death was not reported in the newspapers.

A memorial headstone was erected on Patton’s grave (the location of which was identified by the cemetery caretaker, C. Howard, who claimed to have been present at the burial), paid for by musician John Fogerty through the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund in July 1990. The spelling of Patton’s name was dictated by Jim O’Neal, who also composed the epitaph.

Recognitions

Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton, a boxed set collecting Patton’s recorded works, was released in 2001. It also features recordings by many of his friends and associates. The set won three Grammy Awards in 2003, for Best Historical Album, Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package, and Best Album Notes. Another collection of Patton recordings, The Definitive Charley Patton, was released by Catfish Records in 2001.

Patton’s song “Pony Blues” (1929) was included by the National Recording Preservation Board in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2006. The board annually selects recordings that are “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

In 2017, Patton’s story was told in the award-winning documentary series American Epic. The film featured unseen film footage of Patton’s contemporaries and radically improved restorations of his 1920s and 1930s recordings. Director Bernard MacMahon observed that “we had a strong feeling that the music of Patton and his peers reflected the local geography, and I was struck by the extent to which that belief was already shared by people who were living in the Delta back then, when it was a center of musical innovation. Listening to interviews with H. C. Speir, who owned a furniture store in Jackson in the 1920s and was responsible for virtually all the recordings of early Delta blues, he clearly linked the music to its surroundings.” Patton’s story was profiled in the accompanying book, American Epic: The First Time America Heard Itself.

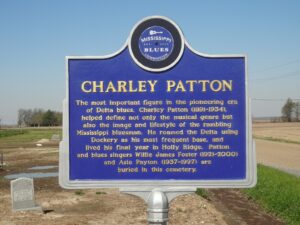

Historical marker

The Mississippi Blues Trail placed its first historical marker on Patton’s grave in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, in recognition of his legendary status as a bluesman and his importance in the development of the blues in Mississippi. It placed another historic marker at the site where the Peavine Railroad intersects Highway 446 in Boyle, Mississippi, designating it as a second site related to Patton on the Mississippi Blues Trail. The marker commemorates the lyrics of Patton’s “Peavine Blues”, which refer to the branch of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad which ran south from Dockery Plantation to Boyle. The marker notes that riding on the railroad was a common theme of blues songs and was seen as a metaphor for travel and escape.

The Mississippi Blues Trail placed its first historical marker on Patton’s grave in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, in recognition of his legendary status as a bluesman and his importance in the development of the blues in Mississippi. It placed another historic marker at the site where the Peavine Railroad intersects Highway 446 in Boyle, Mississippi, designating it as a second site related to Patton on the Mississippi Blues Trail. The marker commemorates the lyrics of Patton’s “Peavine Blues”, which refer to the branch of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad which ran south from Dockery Plantation to Boyle. The marker notes that riding on the railroad was a common theme of blues songs and was seen as a metaphor for travel and escape.