HEY LOCO FANS – Lets sing happy birthday to blues piano player Henry Gray who was born this day in 1925. He is credited as helping to create the distinctive sound of the Chicago blues piano.

Growing up he began playing piano and organ in the local church, and his family eventually got a piano for the house. By the time he was 16 he was asked to play at a club near the family home. After a stint in the Army Gray relocated to Chicago in 1946. He began hanging out in the bustling postwar club scene there, and he got to know Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. In 1956 Wolf asked Gray to join his band. He quickly accepted the offer and stayed on until 1968.

Growing up he began playing piano and organ in the local church, and his family eventually got a piano for the house. By the time he was 16 he was asked to play at a club near the family home. After a stint in the Army Gray relocated to Chicago in 1946. He began hanging out in the bustling postwar club scene there, and he got to know Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. In 1956 Wolf asked Gray to join his band. He quickly accepted the offer and stayed on until 1968.

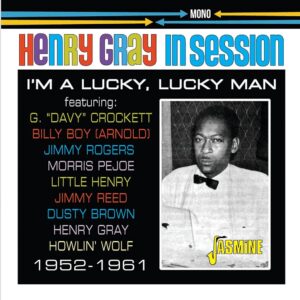

Gray also became a session player for Chess Records, and recorded or performed with Robert Lockwood Jr., Billy Boy Arnold, Muddy Waters, Johnny Shines, Hubert Sumlin, Lazy Lester, Buddy Guy, James Cotton, Jimmy Reed, and Koko Taylor among others.

Following the death of his father in 1968, Gray returned to Louisiana. Gray worked as a roofer for the next 15 years. After returning to Louisiana, Gray performed at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, Montreal Jazz Festival, the Chicago Blues Festival, and the San Francisco Blues Festival. In 1999 he was nominated for a Grammy for his playing on the Tribute to Howlin’ Wolf album.

Following the death of his father in 1968, Gray returned to Louisiana. Gray worked as a roofer for the next 15 years. After returning to Louisiana, Gray performed at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, Montreal Jazz Festival, the Chicago Blues Festival, and the San Francisco Blues Festival. In 1999 he was nominated for a Grammy for his playing on the Tribute to Howlin’ Wolf album.

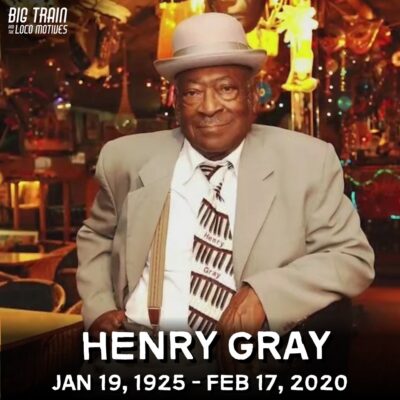

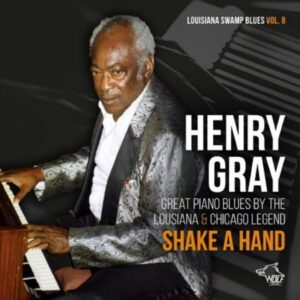

In the 1990s Gray starting recording a string of albums. . In 2017, the same year Gray was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, he brought out the album 92, the title referring to his age at the time it was released. Henry Gray died on February 17, 2020 in Baton Rouge; he was 95 years old. He played for more than seven decades and has more than 58 albums to his credit, including recordings for Chess Records.

In the 1990s Gray starting recording a string of albums. . In 2017, the same year Gray was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, he brought out the album 92, the title referring to his age at the time it was released. Henry Gray died on February 17, 2020 in Baton Rouge; he was 95 years old. He played for more than seven decades and has more than 58 albums to his credit, including recordings for Chess Records.

Gray was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, on May 11th, in Memphis.

Here are 10 interesting facts about the great Louisiana piano man, Henry Gray.

1. The son of a church deacon, Henry Gray began playing piano at the age of eight. Due to the strict Christian attitude of his father, he was only allowed to play spirituals in the family home. He was, however, allowed to play blues in the home of his piano teacher, Mrs. White. By the age of 16, he was playing blues professionally, at a local club in Alsen, Louisiana. Although his father didn’t approve of the “devil’s music,” he became supportive of his son’s endeavors when he realized the money he was making. Deacon Gray then began accompanying young Henry to his gigs.

2. Gray joined the Army at the age of 18. The year was 1943, and he was sent to the South Pacific to fight in World War II. Many times, his popularity from playing piano for the troops kept him from the front lines. After serving three years, he received a medical discharge, and went home to Louisiana.

3. After a brief stay at home, Gray relocated to Chicago. He knew that’s where all the big name blues players were at the time. He also thought that he could make more money playing there, than in Louisiana. In 1946, there were only a couple of young, hot, piano players in the Windy City. One of them was Otis Spann, who had moved there, the same year, from Belzoni, Mississippi. The other, was Spann’s cousin, “Little” Johnny Jones, who had traveled to Chicago from Jackson, Mississippi, the previous year. Soon, all three would have one person in common.

3. After a brief stay at home, Gray relocated to Chicago. He knew that’s where all the big name blues players were at the time. He also thought that he could make more money playing there, than in Louisiana. In 1946, there were only a couple of young, hot, piano players in the Windy City. One of them was Otis Spann, who had moved there, the same year, from Belzoni, Mississippi. The other, was Spann’s cousin, “Little” Johnny Jones, who had traveled to Chicago from Jackson, Mississippi, the previous year. Soon, all three would have one person in common.

4. Major “Big Maceo” Merriweather, had been a Chicago hit-maker for five years when Gray arrived. He had served as a mentor to both Spann, and Jones, and soon took Gray under his wing as well. Maceo taught him the intricacies of using his left hand, developing the “two fisted” playing for which Gray became famous. When Big Maceo suffered a stroke, Gray would appear with him on stage, playing the left hand parts for his friend.

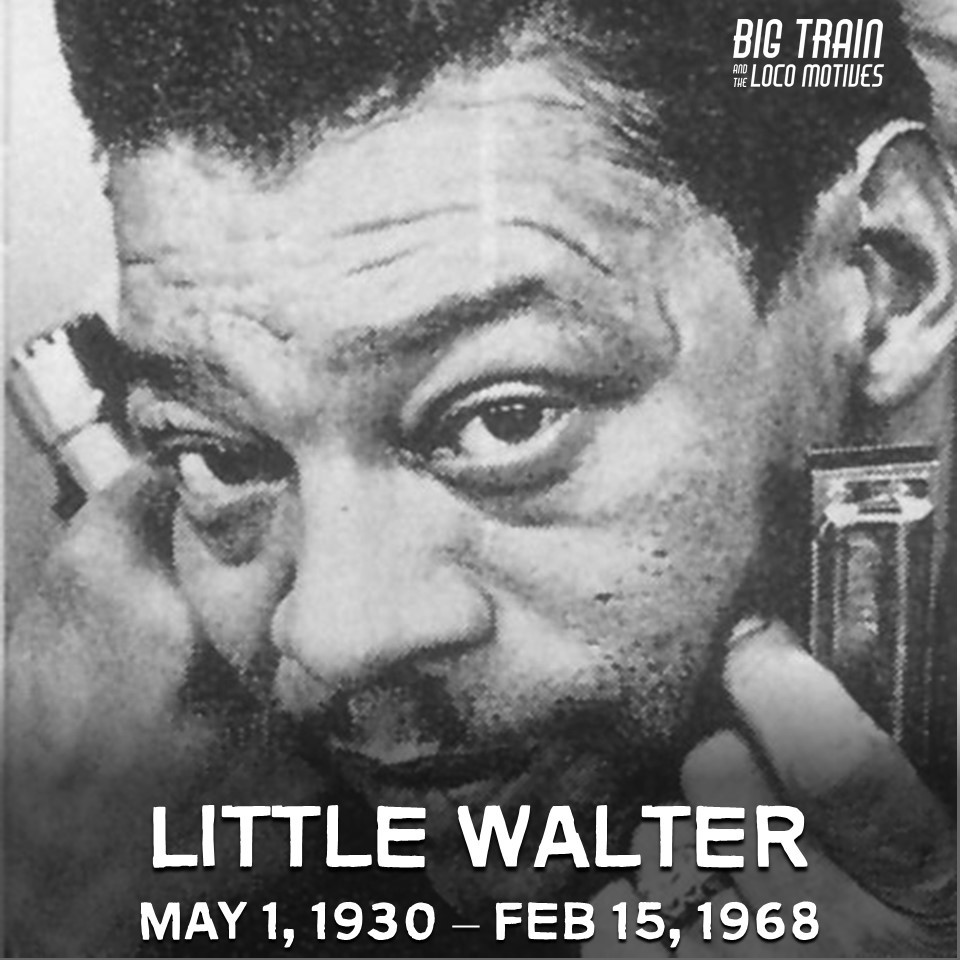

5. In 1956, after years of gigging, and becoming a successful session musician, Gray joined the Howlin’ Wolf band. After guitarist, Hubert Sumlin, Gray’s 14 year tenure, made him the Wolf’s longest lasting band mate. During that stint, he also continued his session work, playing and recording with artists such as Sonny Boy Williamson II, Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Otis Rush, and Koko Taylor. Currently, Gray has over 75 albums on which he is credited.

6. Following the death of his father in late 1968, Gray moved back to Alsen, Louisiana, to help his mother with the family fish market. He also began work as a roofer, for the East Baton Rouge Parish School District. It was a job that he kept for the next 15 years. He never gave up on music, however. It wasn’t long after his return, that he began playing with Slim Harpo. The combination of the two, helped promote the burgeoning “swamp blues,” sound of the area.

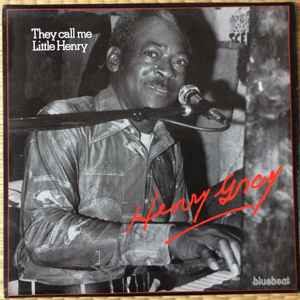

7. After nearly 40 years as a professional musician, Henry Gray cut his first solo album, They Call Me Little Henry, in 1977. Ironically, it was his popularity in Europe that made the record possible. Recorded at Rhenus Studio, in Cologne, Germany, the album was released on the British label, Bluebeat. It was another 11 years before his next album. This time, it was the stateside offering, Lucky Man, on the Blind Pig label.

7. After nearly 40 years as a professional musician, Henry Gray cut his first solo album, They Call Me Little Henry, in 1977. Ironically, it was his popularity in Europe that made the record possible. Recorded at Rhenus Studio, in Cologne, Germany, the album was released on the British label, Bluebeat. It was another 11 years before his next album. This time, it was the stateside offering, Lucky Man, on the Blind Pig label.

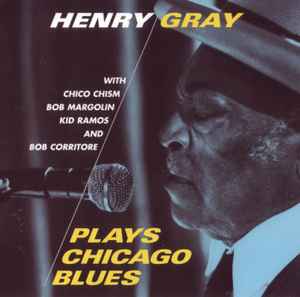

8. Gray has had an ongoing, working relationship with harmonica doyen, and club owner, Bob Corritore. In 1998, they first played together on the album, Wolf Tracks: A Tribute to Howlin’ Wolf. They were joined by other alumni of Wolf’s band, including Sam Lay, Eddie Shaw, and Sumlin. Other guests on the album reads like a who’s who of the blues. Taj Mahal, Debbie Davies, Kenny Neal, Lucinda Williams, Lucky Peterson, James Cotton, and more all took part. The Telarc release garnered a Grammy nomination.

9. So loved is Gray in Europe, that, also in 1998, he was invited to perform at Rolling Stones frontman, Mick Jagger’s 55th birthday party in Paris. The two jammed together, with Gray on piano and Jagger on guitar and harmonica. As a special request from the birthday boy, Gray also played for Jagger’s mother at the event.

10. 2017 was a tough year. Having turned 92 in January, Henry Gray has suffered from both a collapsed lung, and a heart attack. In August, his home was destroyed by a flood. But nothing keeps this last of the blues piano greats down. Recovering well, he still played in the Baton Rouge Blues Festival, and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.